Students, if you are quoting any of the information below for a book report, make sure you cite properly. The latest version of the MLA style guide no longer requires citations to specify the full web address of website sources, however, your teacher may still want you to do this.

Here is how I would cite a quote from this page:

Cardona, James. "My Story." www.jamescardona.com.

Also be sure to check out my BIOpage, my HOW I WRITE page and my INTERVIEWS page for more information about me and the stories behind some of my books. And, as always, feel free to contact me with any questions you have. I love to connect with the readers of my books!

My Parents

Both my mother and my father were voracious readers when I was growing up. My mother still is. My father less so now that he's sick. My Aunt Mollie worked at the Lorain Public Library and I spent a fair amount of time there, which was good because I could pick out the book I wanted to read instead of reading from my mother's or father's stash of novels. My mother read romance mostly but also some horror —stuff by Stephen King or Peter Straub. She wouldn't let me read anything that might give me nightmares until I became a teenager. My father's books were either pulp spy adventures or science fiction. He had the entire James Bond-Ian Fleming series, all of Len Deighton's books, the first one-hundred or so books in the Nick Carter-Killmaster series and many other spy books. In science fiction he had tons of books by Asimov and Heinlein. I particularly liked the robot books but even as a child I knew a robot could disobey the so-called three laws of robotics. That premise seemed silly to me. A robot is just a machine and can be programmed to do anything. It has no morals. It doesn't care about or even consider human life. It has no problem, moralistically, with becoming a terminator and killig us fleshies. In a way, those old science fiction books were more fantasy than science fiction.

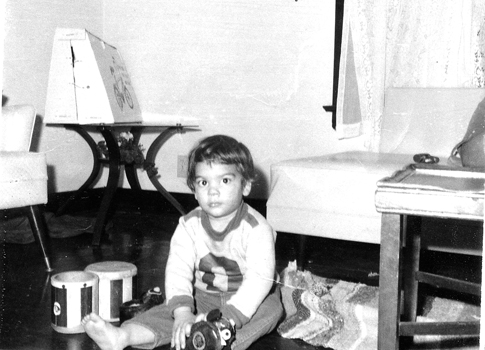

When I was very young I rarely saw my father. He was a workaholic. He had two forty-hour jobs during my early childhood so I only saw him on Sundays and Sundays became a kind of special occasion. We would have a big breakfast, dress up for church and go out afterward to the stores and buy things we didn't need.

Lorain

I grew up in Lorain, Ohio, the home of award winning author Toni Morrison, although I did not know of her at the time. She had left Lorain long before I was born and her style of writing wasn't on my radar as a youth. I appreciate her art now, what she was able to accomplish and communicate. I grew up on the south side of town; she had lived on the west side. One day I would like to meet her.

Lorain, when I was growing up, especially South Lorain, contained numerous tiny ethnic neighborhoods chock full of immigrants. They came from mostly Eastern European and South American countries seeking work. Most of South Lorain, from 28th all the way to 36th street was within walking distance of the city's then-major employer, the U.S. Steel company. My father worked there. The ethnic neighborhoods erupted organically, I think, because people wanted to live close to other people that spoke their same language and shared their same culture. Today, Lorain has a great International Festival every summer where you can sample foods from many different cultures, watch people wearing traditional costumes dance, hear various styles of folk music and just talk to people. It's super cool. You should check it out.

When I was growing up, South Lorain was a front porch kind of town. In the 1970's almost no one had air conditioning, so we did everything outside. In the summer, many families ate their dinners out on the front porch. I wasn't alone in running from porch to porch for a spoonful of goulash or arroz con pollo, a potato pancake or pierogi. The neighborhood kids would gather on the sidewalk to compare notes, to discover who was cooking what and how good it was and formulate a plan, because, you know, you couldn't just line up at a front porch; you had to make it look like you were visiting for some other reason than a quick bite. Somehow I think the adults knew what we were up to.

As a preteen, I wasn't allowed to leave the block or ride my bike on the street, so I would ride my bike on the sidewalk which quickly became extremely boring. I mean, how many times can a kid ride around the block? Those were the days before the internet, video games and the like. To while away the time, I took to playing detective. My friends and I would make up little mystery stories about the various residents and tell them to each other, then spy on the neighbors to discover whose theory was most accurate. We would hide behind doghouses or bushes, spying on the lady in the green house who always left at 5:30pm on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Clearly, she was up to no good, we surmised. Was she plotting a bank robbery? She had no children, wasn't married and always scowled at us neighborhood kids; was she an alien going to report to her squid-like overlords? We would cup our hands over our ears when we walked past her house so she couldn't infect our minds with her alien magic.

Well, after 5:30 was a good time to climb her pear trees and fill our bellies anyway. As we perched in her tree, we speculated that if she uncharacteristically returned early and caught us we might be shot, maybe even with her ray gun.

One day she did return early. Julio, Hector and I were about fifteen feet up. As her silver, rust-splotched Chrysler K car rammed up the driveway, I hugged the trunk close and tried not to move, hoping she wouldn't see my bright-orange, Cleveland Browns shirt. Hector quickly dropped from the tree, landing just in front of the woman's car. Their eyes met. He ran.

"Coward," I spat under my breath. I hated his gall and bravery and that he had exposed us.

She stepped out of the car forcefully, her ancient claws gripping the car window. She crowed, "I'm going to kill you thieving kids! Leave my pears alone!"

It didn't make sense. There was no way she could eat them all. Besides, she never climbed the tree. She never even shook it. The pears just rotted on the branches.

Julio cackled an evil laugh as he shook his branch with his body.

"No, Julio!" I screamed.

Partially rotted pears rained down from his branch, making a smeary mess all over the hood of her car.

The woman rolled her shoulders in an odd inhuman arch then waddled awkwardly toward her front porch. Her left leg didn't fit quite fully into her boot as if her leg appendages didn't belong in a human shoe. Something rumbled across the back of her sweater. Maybe hidden wings, I thought.

I gulped hard.

It was decision time. Should I hop down, branch after branch, and try to escape? I wasn't as agile as Hector. Or should I stay in the tree in hopes that her wings were useless, a mere left-over from some generations-past alien evolution? While I weighed the merits of each of these two strategies, Julio climbed down. I didn't realize he was going to try to escape until he sat perched on the lowest branch. He dropped from the tree and hit the ground just as the old woman emerged from her front porch, shaking her broom over her head in a clawed hand.

"See ya latter, Sucka!" Julio screamed up at me and ran.

The old lady paced in front of the tree with her broom for some time, waiting for me to come down and receive my punishment. I continued to eat pears.

After a time, several hours at least, the sun started to set. I heard my mom calling my name from down the block. Stuffed with pears, my stomach had been hurting for some time. I had to go to the bathroom. I refused to show the woman anything but a stoic face. Somehow, her resolve hardened mine. We were in a standoff. Who would flinch first? I knew I wouldn't.

My mother's voice rang out again. I squeezed my legs together. Staring down at the women, our eyes met. She shook her broom at me a few times. Shake. Shake. Shake. She scowled hard, then her face froze. Something in her eyes softened. She let the broom fall to her side. She turned and went inside her house, dragging her awkward left leg behind her.

Her silhouette hung in the air just past her screen door. It was a trick, I knew. My mother's voice rang out again, calling me home for dinner. I couldn't hold it back; I squeezed my legs together harder. I glanced at the screen door again. It seemed as if she'd disappeared. Was she still there? I quickly descended and ran.

The old woman watched me leave from the shadows.

Mrs. Januzzi

It wasn't until sixth grade that a teacher really impressed upon me the importance of reading, to think about what was read and how words could change a person, that we could actually learn and grow from reading about someone else's experiences. Really, that books and stories contained a theme or a lesson or a secret thing the author was trying to communicate and that good fiction never openly communicates the lesson but hides it like my grandmother who shielded her ginger cookies in the folds of her dress. The lesson, then, is hidden and, in a way, inseparable from the story.

My sixth grade teacher was Mrs. Januzzi and she loved to read to us kids and encouraged us to bring novels to school to read during break times or when we completed our work. She gave us extra points for book reports and let us pick whatever book we wanted (within reason, of course). At first, it was a little disconcerting to be called on in front of the whole class and asked, "Whatcha reading?" She would ask follow up questions about the plot and character motivations. She especially liked to ask why. Why did he kidnap the girl? Why did she jump off the cliff? Why? Why? Why? It got us thinking. What does it mean? Why do you think he would do that?

There was a lesson there, but the lesson was buried in the story and I think she knew that the lesson wasn't supposed to be separated from the story. To truly learn one must experience. A good story re-creates an experience that illustrates a lesson. To be told is to not experience. To experience one must touch and feel and hear and smell and taste and see. Once one experiences something deep and heartfelt, it is as if the thick velvet cloak is ripped away and the light of revelation streams down. That's how we learn the most important lessons.

She read to us in class. It was a Catholic school so she often read out of the Bible, but she mostly stuck to the exciting swords-and-sandals stories in the Old Testament: Jonah and the whale, Samson and Delilah, Abraham and Lot, Noah's Ark, and so on. Every once in a while, she would dramatically close the book and scan her eyes across the room and say, "And the plot thickens!" We never wanted her to stop.

My Sister Lee

My sister was born one year and eight months after me and once she arrived, my father's endless comparisons started. Unfortunately for me, my sister excelled at pretty much everything she touched. She always received straight As in school along with glowing reviews from her teachers. Her artwork was always chosen for display at the mall or sent on to some regional competition. She was even good at sports. It didn't help my ego that my father always preferred girls and openly and unabashedly gave her preferential treatment. I hated receiving any type of school review or report card because he always laid out the two next to each other and asked me why I couldn't do better, like my sister. Instead of being proud of her, I developed an intense hatred and secretly relished the day she would fail. But she never did.

I came to hate these comparisons so much that I stopped sharing my meager accomplishments with my parents and became obsessed with activities not easily be measured. Any school-based activity was out. I quit the chess club and did not try out for sports. Instead, I poured myself into dance, art and music, all of the non-mainstream variety. I wanted to be myself! I didn't want to be compared to anyone else!

Through all of this, my sister supported me and maybe even looked up to me. I overheard her bragging about a remix I had recorded to her friends more than once. When someone walked by wearing a jacket that I had painted, she nodded to her friends knowingly. I think she wanted me to be more of a big brother. Closer. Less aloof. Isolating myself from her is one of my regrets.

Turtle Pond

My father loved to spend his money and loved to show off the latest gadgets he purchased. My house was the first one on the block with a telephone that had long distance service. Some neighbors paid him to use our phone and, of course, I would camp out in the living room and listen in.

We were also the first with a color television. One of the only shows in color at the time was The Wonderful World of Disney and that aired on Sunday evening. Our living room was always full on Sunday evening in those days.

One day, my mother determined, after much begging on my part, that I could leave the block. My friends had found a most magical place called Turtle Pond and I was eager to go there. It was located between a large wooded area and the back end of the B&O railroad property, so us kids would stealthily sneak among cabooses and rail-car grain hoppers to reach Turtle Pond. The pond was full of tar and chemicals and glistened orange and green, kind of the way automobile antifreeze looks when it's new, right out of the jug. Turtles and all sorts of reptiles and vermin inhabited the pond. We fastened rotting plywood sheets on top of old car tires to form rafts that we could move around the pond with long wooden push rods. Initially our goal was just to catch turtles, the more ferocious the better. Snapping turtles were an especially good catch. But one day, spontaneously, the raft battle began.

Julio and I saw Tony and his younger brother, Pepo, who was my age, and a few others that always followed him around like dryer lint attached to the back of his shirt.

"Shhhh, don't say nothing," I said. Julio had just spied a big turtle; we didn't need the competition.

"Well, well. Look who it is," Tony bellowed.

"Catching, Tony?" I said.

"Always." His eyes scanned across the bluish-orange iridescent sheen coming off the water.

"Heard you got Centipede," Pepo said. His breath reeked of onions.

Julio nodded ferociously. "Yeah, he got it. First one. We played today." He beamed a smile.

Tony's eyes tightened in my general direction. I looked away.

"His dad always buys him the latest Atari cartridges. Got them all—"

"Shut up, Julio," I hissed between my clenched teeth.

Tony's face contorted. A sneer was forming.

Julio ignored me. "Tank Battle. Asteroids—although that one is not as good as the arcade. Yar's Revenge. Have you played that yet? No one has. He's got it."

"Shut up, Julio!" I said.

Everyone looked at me. I pursed my lips then mumbled, "We're here to catch turtles, right?"

Tony motioned at me with his chin. He was a whole head taller and about fifty pounds heavier. "Yeah, rich kid. That's what we're here to do."

I edged two car tires into the water and flopped the rotting plywood on top of it as the others watched. "I'm not a rich kid," I said without looking back. "My dad just buys things. I didn't ask him to. He just does it. I don't know why. Your dad... he probably saves his money..." I looked back at Tony for acknowledgment. He was seething, which, I knew, was very, very bad. Tony was the type of kid that held magnifying glasses above ants, roasting them alive. He was the type of kid who liked to catch spiders so he could pull their legs off one by one. He was the type of kid who liked to catch squirrels so he could cut their tails off and release them back to the trees to bleed to death. He had a whole collection of squirrel tails.

Julio hopped on our raft. I boarded and push-rodded it out into the murk using a broomstick. Tony and the lint balls made another raft and followed us.

I didn't want them to see where the big turtle was so I pressed the raft to the far corner of the pond, far from the big snapper's bobbing head.

Tony pushed his pole into the muck, following us close, too close, me looking back, trying to avoid him. He smashed the edge of his raft into ours. The jagged edge of his plywood slid under ours, shifting one of our tires. Everyone jostled. Only Tony and I had poles to steady ourselves.

"Hey! What are you doing?" Julio yelled as he grabbed my arm to prevent himself from falling into the tar-water. I pressed my pole into the mire and spread my feet wide, attempting to stop the raft from shifting into the reeds where it would most certainly get stuck.

The lint balls cackled.

Tony backed up his raft and slammed it into ours again, a leering grin painted on his face.

"Hey! Stop it!"

I pulled my short pole out of the water, instinctively, and held it up like a baseball bat.

Tony's face changed. It lightened as if he had just seen something, a realization maybe, something that gave him immense pleasure. In one swift, flowing arc from the water to my body he swatted me with his pole. The strike stung.

"What the hell..." I swung back. He deflected. My pole hit Tony's. A stream of black tar muck splattered the lint balls. Some went in one of the kid's mouth.

"Get him, Tony!" he screamed.

Tony's nose wrinkled then he swung low.

I shrugged at that. His swing was not even close to hitting me. I easily avoided it by stepping back to the edge of my raft. The rotten plywood splintered and cracked, easily tearing a quarter of our plywood sheet away. The chunk sank. It was then that I realized he didn't intend to hit me; he was trying to destroy our raft.

I tried to push away, into the reeds. Tony bashed our raft again. Another chunk broke off and sank. Julio clenched my arm. The raft wasn't big enough for two. He teetered, looking at me wide-eyed, then leaped onto Tony's raft and grabbed the arm of one of the lint balls. The lint ball pushed him away, but allowed him to stay on the back edge of their raft.

"Come on, Tony. I got nothing against you." I smiled, innocent-like.

I wanted to stare at Julio, to condemn him in a most heinous condemnation but my eyes had no time to wander from Tony because Tony was pressing his raft towards me, a glint in his eye and a grin on his face. He intended to sink me.

"Come on, Tony. What's this all about?" I asked as I jabbed my pole forward at him, attempting to slow his advance. "What did I ever do to you?" I tried to sound young and maybe even a little pathetic, like his whiny younger brother who I detested. Maybe Tony would realize what he was doing was wrong. I was going to attend high school in the fall; he had just graduated. I was just a kid, just starting out and he was going to end my life, because, hey, that water was toxic.

Maybe Tony had no future. Maybe his girlfriend just left him. Maybe he was taking out his life's frustrations on me. Or maybe Tony was just a jerk. Yeah, that's it, I decided.

He closed in. I jabbed, futilely. He swung, smashing my raft, splitting the frail wood plank in two. One of the tires shifted. Tony poled it away. His expression hadn't changed. It was etched on his face, focused, concentrated.

The lint balls cheered. Julio only stared, slack-faced. I was furious in my helplessness.

I waited for the final blow. One more strike and I would surely go down into the murk. Then, amazingly, Tony pressed his raft away. I stood, barely balancing on the single tire—the plywood was useless so I kicked it away. Tar-water splashed up onto my feet and ankles, soaking my shoes, new blue pro-keds with a neat white stripe that my father had just bought me, knee high white socks and pants. I wanted Tony closer, then. I wanted him to push-rod his raft back out to me, just get closer enough for me to leap onto his raft. If he did I would scratch and punch and claw and swing and grapple myself onto him and pull both of us into the tar-water. I didn't deserve this! I didn't desrve any of it. Something happened to him, I reasoned, something I wasn't responsible for and now I was paying the price.

Tony pressed his raft back to the launch area, a piece of land that sloped down from the train tracks to the pond. He leaped off the raft, abandoning the others.

I carefully pushed my pole into the mud, trying to steer the tire across the pond, but the tire wouldn't go straight. Steam seemed to be coming off the pond instead of mist. My head was boiling. Each time I pushed, the tire would spin in place, twisting me, nearly causing me to fall. By the time Tony reached the train tracks, I had made it to the middle of the pond.

Pepo said, "Are we just going to leave him out there?"

Tony sneered at his little brother.

Pepo said, "But he's got Centipede..."

Tony snorted, staring down at the ground. He slowly stooped over and picked up a chunk of gravel. He stood, smiled at me, and hurled the rock. It nearly hit me.

"No! What are you doing?" Julio said as he scrambled up the embankment.

Tony hissed at the lint balls, "Hit him." A command.

The lint balls and Tony began firing rocks at me. I felt like a carnival target. The lint balls couldn't throw very far—maybe they were trying to miss me, maybe they're hearts weren't in it—but Tony could.

Tony barked at Julio who was just standing there. Julio picked up rocks and threw them too. His rocks fell well short.

I alternated between using my broomstick to try to make it to the launch area and trying to swat Tony's rocks away. I dreamed of the perfect connection, the broomstick striking the rock at just the right angle and just the right velocity to send the rock all the way back at Tony. Then one hit me.

Maybe it was the sun in my eyes, maybe I blinked, but I never saw it coming. A chunk of gravel hit my shoulder. It started bleeding immediately.

I screamed in blind fury. Tony laughed.

Another rock hit me. Then another. I was too close. I pushed the spinning tire back toward the high reeds. A fat turtle stuck his head out of the water and opened his mouth at me, staring with black eyes in judgment.

I would kill him then, I thought. Tony must die. As the rocks pelted around me, just out of reach, I plotted how I would do it. I couldn't fight him; he was too big. I needed some sort of weapon. Then it came to me. Endo had a gun and Endo was crazy. Endo was the kind of kid who liked to point his pistol at random people, laughing. His explanation would be that the gun wasn't loaded. Sometimes he would pull the trigger and laugh hysterically when people flinched. Maybe he was crazy enough to give it to me.

Once I neared the reeds, I was trapped. There was no exit point at the back of the pond. No escape. Another rock hit me and I slipped off the tire, plunging into the murk. In the distance, I heard cheering. I abandoned my pole and swam through the tar-water. Cursing.

So it was settled then. I would stomp over to Endo's house covered in black tar. I would ask him to borrow his gun. I wouldnt explain. All I needed was one bullet. Then I would stomp over to Tony's house, knock on his door and shoot him in the face.

Pressing through the reeds, I emerged and ran, covered in slimy tar. Once I was out of sight, the rocks stopped flying. I edged around the tall reeds. The others couldn't see me. I wanted to jump out at them, to run, flying at Tony, attacking with my small fists, but something held me back. I watched as Tony stuck his hands in his front pockets and stared at the ground. He wasn't celebrating; there was no victory in his eyes. He seemed almost... sad. Distracted, maybe. The others walked behind him silently.

I cursed myself under my breath for thinking I would actually go ask Endo for his gun.

About twenty years later, long after I had moved away, I got a call from a friend. After laughing long and hard about old times, he told me Tony had died of an overdose. Endo was in prison for accidentally shooting someone. He didn't know who. I felt a tear welling up in my eye after I hung up but I didn't know for who I cried.

Being An Outsider

There is a saying that all writers are outsiders as if a person needs to be outside of something to be able to see it clearly. Supposedly being an outsider gives one perspective. I do not know if this is remotely true, but in my case I have felt like an outsider pretty much all my life.

My mother is a coal-miner's daughter from Kentucky, one of ten children. My father grew up in a group home for orphans in the Bronx. If you have read my book, Santa Claus vs. The Aliens, you know a little about where he lived. My parents came from two different worlds and I never completely felt a part of either of them. My father didn't know enough Spanish to teach me so I was an oddball in the latino community, yet my skin was just a little too brown to not stick out among my fair-skinned, freckled cousins.

I went to private school until tenth grade, St. John's Elementary and Lorain Catholic High. I fit in relatively well in grade school, but only a handful of students were from south of the tracks at Lorain Catholic. Again, I felt an outsider. Several times I was questioned when lockers had been broken into or a wallet or backpack went missing. I had nothing to do with any of the disappearances, but, perhaps, my brown skin and where I lived always put me on the short list of suspects. A handful of black and otherwise non-white students attended Lorain Catholic on sports "scholarships." At the beginning of my freshman year, a girl asked me what sport I was going to play alluding to the fact that non-white people at the school were clearly only there to win on the football field or the basketball court. She seemed confused when I told her I was planning to join the band. She wasn't the last person to ask me this question. Thirty-five years ago and a different time, I guess.

Sports weren't for me, not only because I wasn't generally good enough to make the team, but it felt too mainstream to me. I felt like I was only adding to a statement that was already made instead of being able to form my own voice. As I mentioned previously I embraced any type of artistic expression that wasn't considered mainstream. I know that now, anyway. At the time I would have just said that what I was doing was cool. I really didn't understand at a deep level why I was doing the things I did. Once I became good enough at grafitti that people began to recognize my art, I started a healthy business of selling clothing that I had decorated and painted. In the 1980's grafitti developed a poor reputation as vandalism since many of the aspiring artists painted on buildings. I didn't do this. My art was drawn on clothing and sketchbooks and canvas.

In my mid-teens, I tried my hand at deejaying. I was fascinated by the ability to create something new using the raw materials of prerecorded music. Throwing two, three or four songs together, simultaneously, to create something completely new and different, something that I could touch and channel with my finger in real-time was incredible. Sometimes something novel and unique would happen, something I hadn't planned, organically, and fusion of two sounds that I hadn't predicted. It gave me goosebumps. I had a few small stints as a night club deejay in my early twenties, but I tended to disagree with the club owners. Their focus was on pasking the clubs with money-paying customers who would buy drinks. My focus was the music. Always the music. The sound. The experience-transcendental I fel at the time. I was too experimental, they would say. I could pack a dancefloor, but the owners wanted me to play some wacky radio music once in a while. Clear the dance floor, gives the customers an opportunity to buy drinks. I just couldn't do that. Was it my fault the owner couldn't feel the groove? I didn't last too long in anyone place and eventually quit.

The mid-1980s were tough on the steel industry and a union-management disagreement devolved into a strike and then a lockout at the U.S Steel plant in Lorain. With my father out of work, my parents could not afford to send me to private school anymore so I transferred to Southview High for my last two years. I hoped I might fit in there. I didn't. Being an outsider, I think, is a matter of perspective and position and once a person becomes comfortable in that role, the person tends to gravitate toward it. Perhaps I was beginning to imagine myself as an outsider when I didn't need to be. Maybe I always did. At Southview, I was a new kid which is a precariously place to be at sixteen. Everyone else knew each other since kindergarten. The only people I knew were the handful of kids who lived in my neighborhood and a smattering that had attended my grade school.

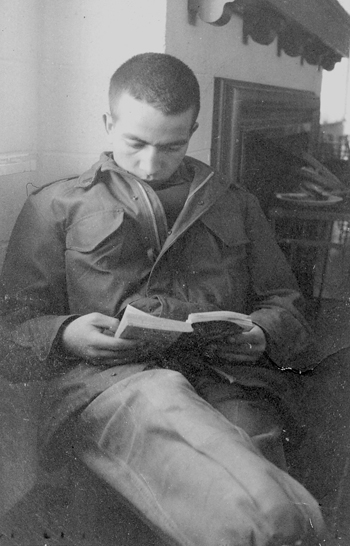

Up until this point, I only saw the disadvantages of being an outsider. It wasn't until after high school, when I joined the US Navy, that I realized the advantages. In the military, everyone is initially an outsider. We all came from different places and had different experiences. In boot camp, there were a handful of recruits that had been given the choice between military service or prison. Some others were, like me, fresh out of high school. Others were deep in their thirties with a lifetime of experiences under their belts. A few were foreigners who thought they had a chance at citizenship through military service. Finally, I understood.

Being an outsider, no one knows who you are. You can reinvent yourself. Change. Become someone without two luggage loads of history.

In the Navy, after hours the men told stories about where they had come from and what they had seen, each more grisly and harrowing than the next. One was a member of the street gang in Los Angeles. He said a rival gang was going to kill him the night he left for the military. Another, from rural South Carolina, caused a multivehicle accident while drunk driving. He escaped to the military too. It seemed like most were trying to evade or avoid someone or something. Others reveled in their past glories to demand respect as if they had completed a rite of passage and now wore some invisible badge of honor. One claimed to be a champion black-belt fighter. Another said he was a CEO of a company. Each claim was more audacious than the previous.

All these stories of the past lives made me think. I remember the long quiet hours on the tarmac, contemplating temporality. Things that burned so brightly in my memory were completely unknown to other people present when the event happened. The past, it seemed, was molded by imperfect memory. It was malleable or could be created from the ether by the teller. And since the future is unknown I decided to not waste too much thought on it either. All we have, I determined, is the present.

The great poet Rakim, partner of Eric B., said, "It's not where you're from; it's where you're at." Ella Fitzgerald said something similar: "It isn't where you came from; it's where you're going that counts." I would alter the sentiment: It's not where you're from; it's who you are. For me it all comes down to value systems and how we measure each other as human beings. Everyone has the ability to reveal what they are, inside, and although much of what forms a person is past experience, who we are is more about our reactions to those experiences than the experiences themselves. The sailors I met told stories to increase their value in the eyes of others. Instead just be who you are. Be valuable.

I am still an outsider. But only because I choose to be.